Sacred Chickens

Menu

SACRED CHICKENS

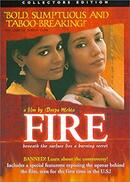

Here is an essay I wrote on the movie Fire by Deepa Mehta Fire is an Indian Film that I watched as part of my Feminist Theory class and I wanted to share some thoughts I had about it on the blog. I think it’s definitely worth a watch. Although there are certainly cultural differences, much of the underlying assessment of patriarchal power structures has global significance. The following is a paper that I wrote exploring the ideas in the movie - in case you’re wondering about the slightly more academic style than usual. The film Fire, the first in a trilogy by Deepa Mehta, focuses on exploring a homosexual relationship between two wives in loveless, arranged marriages, which is a primary example of compulsory heterosexuality, which as “Sets itself up as the original, the true, the authentic; the norm that determines the real,” (Butler, p. 317). The film is a harsh critique of Indian culture as a whole, but these attitudes and prejudices are not unique to India; they can be found in nearly every part of the globe. Not only is Fire a societal critique aimed at dismantling, questioning and rebelling against patriarchal culture, it is also sending a message of empowerment to the women who watch it. Throughout the film, the viewer is shown that the women are only ever important in serving a man’s needs. She herself is not important; her sense of self is wholly tied to the man she’s married to, and she has no real identity to speak of. This subjugation and domination is one of the main things that Deepa Mehta is critiquing in her film. By bringing the focus and attention of the film away from the men, who, although they are the main power brokers of society, are really side characters in the film, Mehta is showing that women can write their own story and decide for themselves who they want to love and how to live their lives, even if they have to pass through fire to do it. Women being subjugated and dominated by the patriarchy is perhaps one of the more obvious messages in this film, but it’s still important to note that the entire culture is inherently phallocentric. Nearly all aspects of the society are to the benefit of men, and the detriment of women. The patriarchy has a vested interest in keeping women in this position if it is to maintain its power. Heterosexuality has been, “Forcibly and subliminally imposed on women,” (Rich, p. 120). Much like religion, it relies on early childhood indoctrination to maintain its authority and promote its ideals. Women are taught from a very young age, not by their father as one might think, but by their mothers. Ironically, it is the mothers who teach their daughters their place in society. They pass on an internalized sexism that may not even be verbally communicated; just being withheld an education, being told who you’re going to marry, constantly being at the service of men and seeing your own mother in a position of servility can instill these damaging ideals in a child’s mind. Again, some of these things, like arranged marriages, may not occur within Western culture, but the critique is still applicable, nonetheless. Women are, “not an oppressed minority, but a majority,” (Morgan, p.454). Women constitute half if not more of the world’s population; if empowered and amassed, that is a force that could affect and demand real political and societal change. The two women in this film really are, “Slaves with chains to break,” (Kramarae and Treichler, p.7). I do have reservations about using the term slave to describe Radha and Sita, because of the historical overtones of the word, which I fear is somehow demeaning to horror endured by thousands of slaves in the American South; however, what other term should one use to describe a woman who is completely dependent on a man? She has no freedom, either economic or societal and she is treated as an object and is in essence a servant meant to fulfill the desires of her husband. Religion plays a large role in justifying these attitudes. The film itself is rife with religious symbolism. At one point, Radha’s husband calls her relationship with Sita an abomination. This is language that is also levelled against homosexuals in our culture, as well, and one of it’s main roots can be found in religion. People can argue that it has been wrongly interpreted or taught, or that they personally don’t believe that, but it doesn’t really matter. Two thousand years of biblical teaching cannot be undone by mere personal belief, and it must be recognized that, if not religion itself, Churches and priest have done untold harm towards the LGBTQ community. It is the same in Fire, and indeed the religion there seems to hold even more sway than our own. However, Mehta seems to have a different approach. A trial by fire, echoing the name of the film, has a heavy significance in both the film and Indian culture. It was traditional for widows to practice self-immolation when their husbands died, to avoid any impurities that might be brought about by an unkept woman. Being burned alive, especially by or at the behest of men, is one of the more violent and domineering punishments I can think of. It is really the ultimate form of domination, because of course the fire is all-consuming. As demonstrated by the various Witch Trials found in the history of Western Culture, burning women alive is not only meant to purify the soul, it is meant to invade a woman’s body; it is an extension of the will of men, and the movie demonstrates that. They repeatedly make reference to a certain female deity proving her worth to a male god by passing through fire unscathed. This is mirrored in the experience of Radha when her sari catches fire, and she is abandoned by her husband to be, “purified.” However, she survives and is reunited with Sita. This is Mehta’s way of saying that Radha’s and Sita’s love for each other is divinely blessed, which is different from the teachings so often portrayed by those who claim to interpret the divine. They do interpret and teach, yes, but in a way that ensures their continued authority. This is a film heavily focused on sexuality; whose sexuality is right and whose is wrong, with an emphasis on policing of sexuality and gender in a variety of ways. We see that sexuality is in many ways a performance, a ritual done because of tradition. The women’s marriages to their husbands are done out of love, but out of some sense of cultural duty, a tradition to be upheld. That falseness shows in their interactions; they’re tense, stilted, awkward, angry or indifferent. They clearly do not love each other, and many times seem miserable in the other’s company. Even though they are conforming to societies standards, and doing what they’re supposed to, they know that they are not full members of that society. By contrast, when we see the two women together, they are affectionate, caring and passionate. It’s a radical contrast, which cannot be overemphasized, because it is done intentionally by Mehta to demonstrate what happens when you actually follow your heart, and make your own decisions, rather than having them made for you. Overall, the film Fire addresses many issues that are not only relevant to Indian culture but to Western Culture as well. Deepa Mehta harshly criticizes the patriarchal culture of India and presents and empowering message to women that they do not need to follow the subjugating traditions that society demands of them. She also presents a powerful message about the lesbian relationship that prompts Radha’s and Sita’s rebellion; that it is not only accepted but protected by divinity. It is unsurprising that when it was first shown in India, the theater was burned to the ground. The symbolism of that act cannot be overlooked, given the previous discussion of the symbolism of fire. However, at least Mehta’s work can still be viewed, and her message still shared, so that women not only in India but globally, may achieve the goal to not only, “Change drastically our own powerless status worldwide, but to redefine all existing societal structures and modes of existence,” (Morgan, p. 454). Works Cited Butler, Judith. “Imitation and Gender Insubordination.” Reading Feminist Theory: From Modernity to Postmodernity, edited by Susan Archer Mann and Ashley Susan Patterson. (New York: Routledge, 1991). 317-20. Kramarae, Cheris and Treichler, Paula. “” Woman,” “Feminists,” and “Feminism.”” Reading Feminist Theory: From Modernity to Postmodernity, edited by Susan Archer Mann and Ashley Susan Patterson. (Boston, Pandora: 1985). 7-8. Morgan, Robin. “Introduction: Planetary Feminism: The Politics of the 21st Century.” Reading Feminist Theory: From Modernity to Postmodernity, edited by Susan Archer Mann and Ashley Susan Patterson. (1970 New York: Random House). 452-54. Rich, Adrian. “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.” Reading Feminist Theory: From Modernity to Postmodernity, edited by Susan Archer Mann and Ashley Susan Patterson. (New York: W.W. Norton). 117-123.  Bio Jarad is the co-administrator and writer for Sacred Chickens, attends college at MTSU, loves tea and coffee, and tries to spend every spare second reading. He recently developed an interest (some might say obsession) with gardening. Jarad is an English major with a concentration in literature. Bless his heart! Let's all light a candle for him and send him happy thoughts!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Click Photo above to buy ebook or paperback from Amazon.

Here's the link to Barnes and Noble Or order through your favorite independent bookstore! Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed